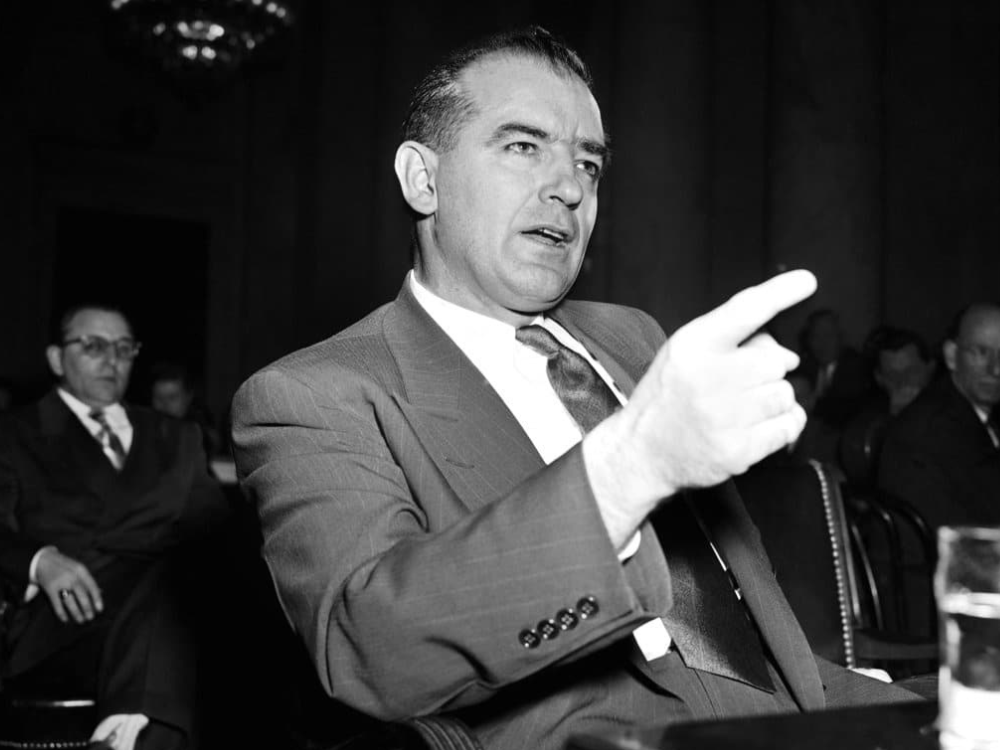

As the chair of two powerful Senate committees, Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy, Wisconsin, seen in a March 1950 subcommittee hearing, was well positioned to make unfounded complaints about the supposed Communist infiltration of the U.S. State Department, stirring up a second “Red Scare.”

Those who consider the wrecking ball duo of Donald Trump and Elon Musk a new and dystopian development in American politics are wrong. Though each man is unique in his own way, both descend, in tone and damnation of restraint, from the “Better Dead Than Red” era of national discourse. The Communists may be gone, but both Trump and Musk have many a parallel witch hunt to spare.

The Communists may be gone, but both Trump and Musk have many a parallel witch hunt to spare.

First, though, let us briefly backtrack.

In a period spanning roughly a decade, 1947 to 1957, and in line with the menacing rise of Stalin’s Soviet Union and the creation of Communist China, an impressive array of American political and business leaders waded neck-deep into what would be called Red-Baiting. The group included a reckless and dangerous senator, Joe McCarthy, and an incipient vice president, Richard Nixon, called to serve as Dwight Eisenhower‘s running mate precisely because of his nasty anti-Communist views. These two men, and many others like them, worked to ruin the reputations of as many of their fellows as they could find, all their attacks, or so they said, in the patriotic name of weeding out the Communist traitors existing like sleeper cells within the ranks of American society.

They were vicious in language and unapologetic in tone. Postwar Europe watched amazed, never imagining a United States quite so dirty but compelled to say nothing as U.S. cash was funding Europe’s reconstruction. Yet this did not seem like the America that had liberated the continent. French philosophers, including Albert Camus, watched this fall into ugliness and concluded the world might not be worth saving. Existence itself seemed corrupt.

There is no understating the mean sweep of the Red-Baiting, nor any way to mitigate its accusatory language. Trump and Musk are chump change when it comes to a movement that made everyone in government and the wider cultural world a suspect. In running for office in California, Nixon repeatedly humiliated his challenger, Helen Gahagan Douglas, with absurd Communist tarring. He won. Decades later, when President Nixon stood accused of Watergate corruption, Douglas wrote in a letter to my mother, “I have no wish to speak of that time. We both know what it was like.” She charitably refused to pillory Nixon, who would resign in 1974.

What made the decade cited earlier so awful and unbearable is that so many major and minor players took up the Red-Baiting baton. Some Hollywood actors were blacklisted, as were journalists. Throughout the 1950s, America lived with, and mostly accepted, a siege mentality.

Only in the early 1960s was the spell broken, with entertainers, including a very young Bob Dylan, mocking the mood by poking fun at those who saw Communists in their cupboards.

Now, Trump and his new best friend Musk insult all they can find, the latter using his newfound political status to express the kind of bile once confined only to social media.

Now, Trump and his new best friend Musk insult all they can find, the latter using his newfound political status to express the kind of bile once confined only to social media. He insults nations and continents, and with his erratic, bully temperament, he is far from done. Little needs to be said about Trump. He proved his congenital cruelty long before first becoming president in 2016. All he can do now is play second fiddle to the raging Musk.

All this is, to say the least, disturbing and distressing, but it is not new. What is?

The groundwork for the Trump era was put down by Newt Gingrich in the 1990s, with the Tea Party movement to follow. The Republican party tried to stay the course, nominating two decent men, John McCain and Mitt Romney, for the presidency. But when both failed, it left the door open for a new “Better Dead Than Red” era, and Trump stepped front and center.

Can such damage be undone?

Progressives despair and shout in the negative. All is lost, they say, though no one floats the idea of an anti-Trump American government in exile, to help balance the table, albeit symbolically.

Yet history suggests that even the worst passes. John Kennedy helped exalt the early 1960s. Barack Obama seemed to come from nowhere following eight years of troubling rule by George W. Bush, who had his own insider Musk in his vice president, Dick Cheney.

Dystopian downs can be followed by utopian ups, although neither is as surefire as they might seem — witness Obama’s fall from grace.

The moral of this story is simple: that the past can at times speak more eloquently than the present, and though to many this may seem the worst of times, something like the best may await us down the line, in three years, not eight. Which is reason enough to hope.