The place where the boardwalk ended, a carpet of stitched-together matchsticks surrendering to endless, disinterred sand, seemed to me like the end of the world. The stretch of wooden plank ceded to sand and dunes and ocean grasses that seemed to whisper, “Come this way, but only if you are Columbus.” This, of course, was my father’s line. He liked places that came to an end. He also described maps of the ocean-abyss painted before the entrepreneurial Italian sailor managed to persuade ambitious Spanish royalty to let him go beyond the beyond, where he imagined roads to riches might lie. They mostly thought him mad and gave him three small ships, an ill-equipped pittance in which to try to navigate the waiting abyss.

Yet try he did and he did not fall off, reinventing the human universe.

So when I stood at the boardwalk’s end, a bold tiny version of Columbus, I finally one day felt a surge of courage and asked my father if I could keep walking, alone, into the dunes and the reeds, along the shore that led to the next town, assuming I was not consumed by a dragon or fell from a dune into the center of the earth.

So on a sunny day in June I walked and walked into this beyond, my father agreeing to let me have an hour of what I called “magic time,” when I didn’t have to play by anyone’s rules. (Some might suggest the magic persisted and persists still.)

The dunes were not like the pictures I had seen of big ones in the Sahara but randomly large or small, often changing in shape as the wind whipped in from the sea like the hand of a sculptor still at work on his many beach projects, slathering the sand so that it moved in all directions.

This was an empty landscape, no houses by land’s end and no people walking the emptiness to keep it company. I was alone.

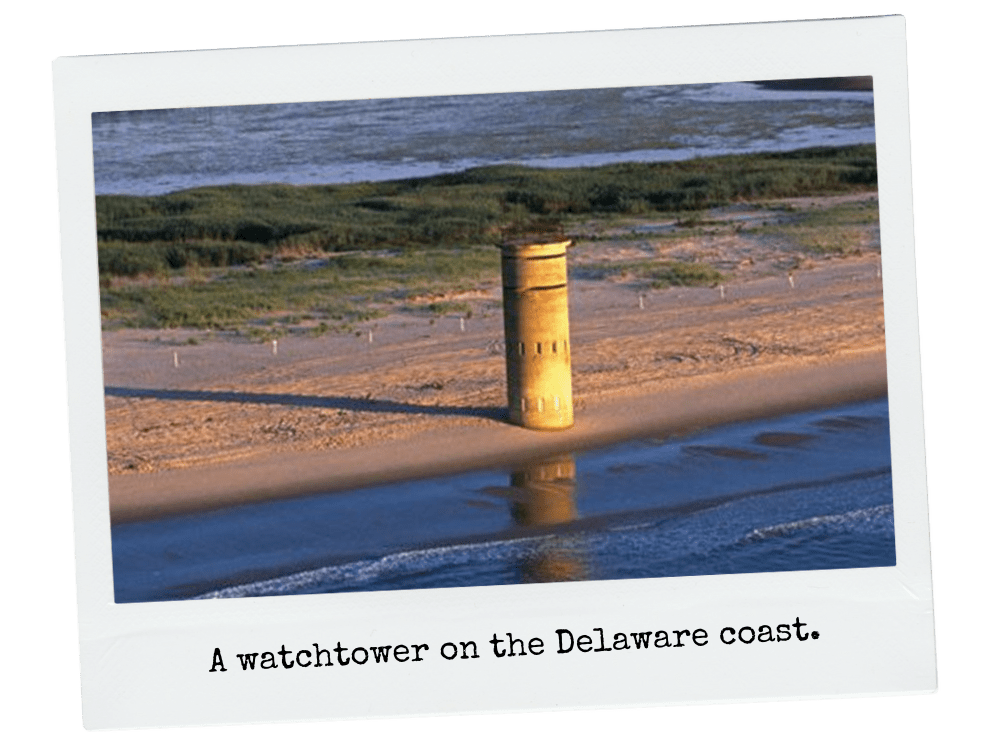

Then, suddenly, as if in the Sahara, a mirage came into focus: three turret-like concrete towers, each about twenty feet high. They clearly had not been touched for a long time, and sandy weeds grew in their crevices. All three had oblong peep holes from which someone inside could peer out the side. Their metal doors were rusted closed. They were built from simple concrete and served no purpose that I could imagine.

My father was unimpressed by the alien hotels and the undersea tunnel. This was my father’s greatest gift, to never leave well enough alone.

As I was in magic time, I considered them, at first, as perhaps alien space ships of the concrete kind that had come to land on human beaches but, once they got stuck in the sand or found the planet so disappointing, they were unable to do much but remain in place, like three fat soldiers on leave.

If they were not alien, perhaps they dated from a time when some tycoon sought to build a tunnel under the Atlantic, linking Europe and America, and these three towers were where the drills would be situated, their bits clawing into the sand and gradually making crab holes across the ocean.

None of this, of course, made any sense or respected logic, but these were not my strengths, not in magic time. I even thought of abandoned circular hotels, but where were the windows?

I was so taken by these structures I lost track of time and soon realized my hour had long since run out, and scampered back at top speed over the dunes, often tripping, all to reach that last plank where my father sat on a white bench, reading a newspaper.

I told him of the alien hotels and the undersea tunnel but he was unimpressed. This was my father’s greatest gift, to never leave well enough alone.

He pried me away from magic time and instead of hauling me back to the cottage to prepare for dinner with my mother at Mrs. Simpler’s place, he clutched my hand and pulled me outland.

“Show me,” he said.

And together we made our way toward the spaceships. I was certain he’d laugh at me once we got there but he did not.

He examined the three turrets carefully, approaching one and pulling on the rusted door, which opened into an empty concrete silo with stairs to a railing near the oblong peepholes.

Submarines, he said.

These were submarines! How magnificent, I thought.

No. These were bunkers built in the early 1940s by the American military and Coast Guard authorities to look out over the sea in search of periscopes.

But why, if these were submarines, would they be looking for periscopes.

Since I was at an age when all is possible, no limits bring the imagination into line with reality because reality in its adult form has yet to exist.

Patiently, my father extracted me from the first tower, closed the door, and pulled me by the hand as we began the walk back.

It was then that he explained, as he would later so many times, the bits and pieces of World War II as lived on the domestic front. Though he’d been in London and Egypt, and been made a colonel to give him security clearance, he knew what domestic precautions had been taken, and these primitive towers along the eastern and western seaboard were among them. They were manned in shifts by the military, with binoculars to check for enemy submarines prowling too close to American shores. In this case, the military was interested in trying to spot Nazi U-Boats, fearing they might try to enter local harbors and torpedo key vessels in what, to some extent, amounted to a suicide mission, since the submarines would be unlikely to get home. Still, long-range U-Boats did make the trip, and that was the reason for the now-long-abandoned towers.

I wanted very much to ask my father what an Axis was and where it got its power, but he had begun walking ahead of me.

This put my aliens and tunnels and hotels to sleep and annoyed my magic, but I had learned a little something, which is what my father intended. He said America’s greatest fear was not submarines but that the Germans might build long-range bombers capable of carrying out strategic missions on American soil. They worried as well about missiles, which the Nazis showed an uncanny ability to develop and fire, though their range was limited. Had the war lasted another two years, the Axis powers very likely could have struck the continental United States.

I listened to all this as Columbus must have listened to Ferdinand, while paying more attention to Isabella.

I wanted very much to ask my father what an Axis was and where it got its power, but he had begun walking ahead of me, back on the wooden planks, back, in his mind, to the history of a war he knew by heart.

I stood for a moment before joining him, still perplexed at this new word, and decided all at once that an Axis would be what lay beyond a boardwalk. An Axis, because of its wonderful “x,” would be the start of the unknown, and an axis a place beyond which lay reeds and clefts of sand and even turrets. An axis, if it indeed came with powers, might even help a boardwalk go on forever, perhaps making a bridge across the Atlantic, which I promised myself I’d build, most likely after bedtime, when most of the world’s great projects, mine foremost, were best accomplished.

— This is one in a loosely linked series of autobiographical essays in which the author recollects his childhood years, spent largely in Washington, D.C., and Madrid, Spain. Some names and details have been altered for reasons of privacy.