Beach life came with pleasures and admonishments, the latter (including the widespread failure to venerate my castle projects) I simply disregard — in exchange for requisite doses of cotton candy.

On most early mornings I’d walk with my father under the lifeguard tower — this so he could greet the young man on duty with a nod and a hello, a prelude to staking out a spot for our towels and chairs.

The lifeguard he most respected was named Chet, grandson of a man from a strange land that ended in “slavya,” a land that was, of course, not strange to my father. This “ya” land was apparently ruled by a man or thing named Teetoh, which made me think of flakes and chips whose names had a similar lilt.

This “ya” land was apparently ruled by a man or thing named Teetoh, which made me think of flakes and chips whose names had a similar lilt.

Chet grew to respect my father and thus made a special effort to look out for me. This included warning me on days when there was a strong undertow.

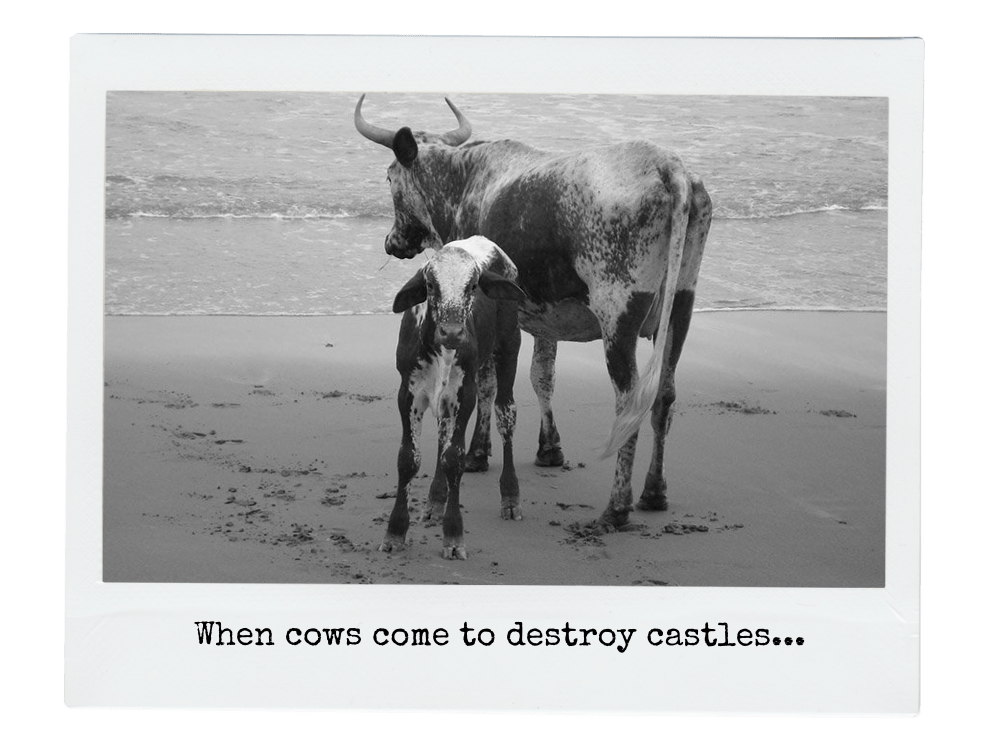

This, of course, I understood no better than Teetoh, and came to wonder just how a hidden sea toe could by itself take control of an ocean on any given morning, eliciting admonishments about swimming out too far. Chet did tell me the toe was strong enough to pull a cow to sea, and this made me imagine a toe, or a series of toes rising up from the waves and dragging grazing cows from their pastures into deep water. I’d laugh at this, leaving Chet bewildered at my refusal to take danger seriously.

“Fearless little kid,” he’d tell my father. In fact, I was anything but fearless, worried about the possible presence of carnivorous sea creatures and cows that might return from the toe to trample my castles.

But after much thought I decided I would refuse to be daunted by a toe. One day I told this to my father following a warning from Chet. Suddenly, all changed. He grabbed my hand, sat me down beside an incipient castle, and explained the mysteries of the toe, the real undertow, and made it clear Chet of the Slavya heritage was not joking.

Though I understood the undertow concept more clearly, I still stubbornly refused to accept it had any sway over me, strategist and castle-erector.

Until the “Incident of the Log.”

The Log was a wonderful hot-dog-like inflatable raft toy I’d been given as a present. Every time I waded into the Atlantic, the Log was at my side, an ally and loyal protector.

The Incident came to pass one weekday when I chose to wade just a little farther out than usual, past the first slap of incoming waves.

All at once the Log began to drift away from me. The more I swam toward it, the more it receded out toward deep water, as if tugged on by an invisible rope. The betrayal was incomprehensible.

Finally, I heard Chet’s whistle: I should swim out no further. Devastated, I sulked crying back to shore.

Chet then went to work, swimming hard and fast out toward the outward-bound Log, his athlete’s body cutting through the buttery surf. But the Log was now both sea and windblown, and Chet was defeated. The tow (still toe to me) and tide had together cast a spell on the Log, which was soon far, far out of swimming reach. Even Chet had limits beyond which he was not allowed to swim, lest he set a bad example for mortals on the beach.

My father bafflingly told me that losing the Log should be seen as an admonishment as well as a metaphor for hubris. Hubris, he said, was thinking you controlled all you wanted to, never mind human limits. He told of a man with “dead” in his name and another called “ick,” at least in part. Dead and Ick. Determined to fly, they made great wax wings, and fly they did. But the sun was unamused by this hubris and melted the wax. They fell.

I was sorry for them, but sorrier still for myself, now bereft of my Log. As for hubris, more was to come, and more lessons would be learned.

Dead and Ick. Determined to fly, they made great wax wings, and fly they did. But the sun was unamused by this hubris and melted the wax. They fell.

My mother reassured me we’d get another Log, but I insisted I had but one partner, now lost at sea. All of this because of the mean toe.

I mourned the Log for days on end, wondering why I missed it so. I finally concluded it had been my friend, a version of me, filled with my air from my lungs, and this consoled me because it meant the Log had probably decided to seek out its own adventures, and thus was taking me on a kind of trip. Maybe one day my inflatable friend and companion would determine vagabond days were over and return home.

Within a week, after further castle triumphs, bits of pizza and cotton candy, thoughts of the Log diminished and I bid the Log farewell in a special bedroom ceremony in which I cursed the toe but wished my friend safe travels.

And though Chet always made a point of warning about the toe, life went on.

— This is one in a loosely linked series of autobiographical essays in which the author recollects his childhood years, spent largely in Washington, D.C., and Madrid, Spain. Some names and details have been altered for reasons of privacy.