Our yellow cottage was possessive of its rooms. It had but three: a large bedroom, a smaller one, a cupboard-sized study, as well as a kitchen counter that was all but wedded to the sofa, as if the two had known each other for decades. I believed the cottage spoke in voices. When my father attempted to make the cupboard his study, a gust of wind arose from the sea and slammed the door not once but twice. It was then that I entered the cupboard and made it my bedroom. I aligned things in such a way as to elude the cottage’s wind-enticing caprices. I made the tiny bed my own, a sliver of stubby old softness. I placed it just under a window, placing a thick splinter of wood under the eager-to-slam door. The window, moored by ropes, opened into a bush of flowers with thorns that were not roses but something else, something more like a creeping vine, dark and gnarled with fat, sharp thorns. I so much liked this gnarled vine, I had no wish to know what it was called. In that time of smallness I had only my own whimsical vocabulary, and that year in the late 1950s could have as easily been a year in the late 1350s, because I paid no attention to these details.

I was too short to even stand and play a pinball machine, content instead to wander among what my father called “the hubbub,” which I thought might be the adult word for the small Funland amusement park. I did try to talk with the cotton candy man, who spoke a little French because he’d been born in French “Kebeck,” which he never explained. I thought perhaps this Kebeck was a town near the sea where, for whatever reason, those associated with candy spoke French. Later, my father told me of Montreal and Quebec, but, as with my love of the mysterious sprocket vines, I set the knowledge aside for when I’d become old, seven or eight, say.

Kebeck was a town near the sea where, for whatever reason, those associated with candy spoke French.

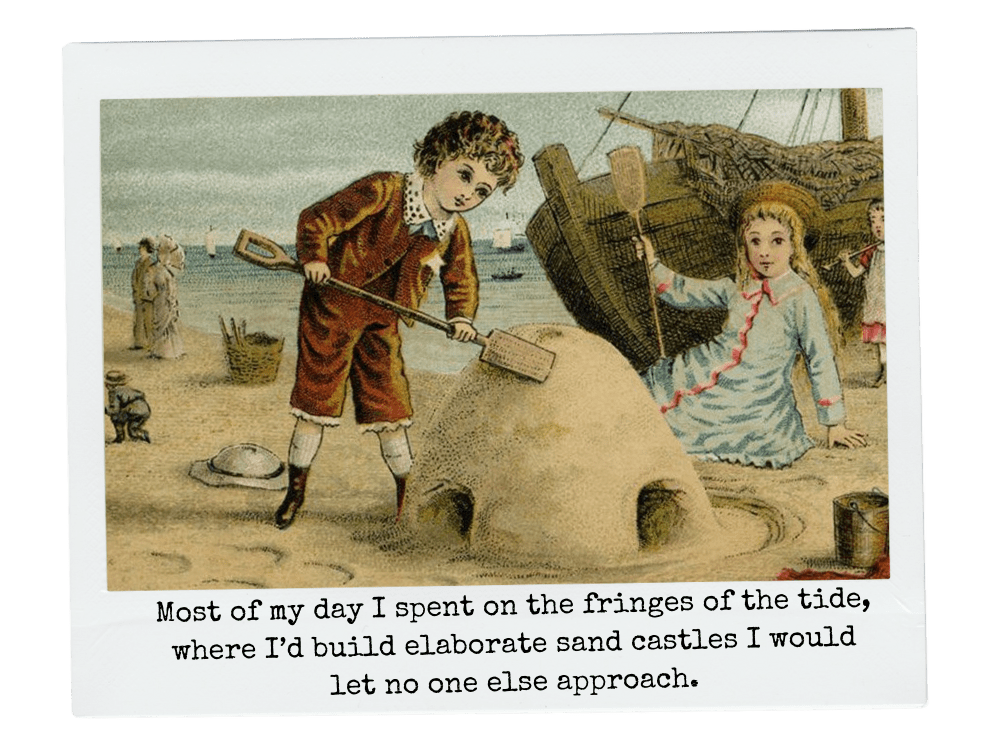

Most of my day I spent on the fringes of the tide, where I’d build elaborate sand castles I would let no one else approach lest they distract me from my latest turret and the twigs I had collected from nearby fields to act in the stead of cannons. I was a tiny military strategist of the highest order, consumed with building his empire, which all the world awaited to see at its peak, at least in my mind. All I made I assumed would later win the praise of my elders, men and women alike, those who occupied the space my father called “real life,” a real life that at that time was foolishly uninterested in the magnificence of my meticulous beach work. The value of my enterprise they could only learn over time, evidencing a principle defect of adults: they failed at excitement, or had forgotten how to understand it.

As for my castles, I wanted them to reflect the perfection of some great gift of craft I could set against a father or a bus driver or an ace pinball player. My enemies in these efforts were the tides, relentlessly disrespectful of my perfect parapets and barracks, nibbling away at some, destroying others. I would yowl when this happened, startling other beach children and leading my father to quietly suggest that to insult the tides and oceans was a pointless exercise, since their dominion, and wants, were even greater than mine, something I found at the time unimaginable. I wished all at once to live in Kebeck, with the candy.

Worse than the tide for their living insidious nature were the sand crabs, round insect torpedoes moving like small determined demons through the sand and coming up all at once in one of my castle channels or undoing a tower. I wanted them all committed to dungeons, banished and imprisoned, but they, like the sea, responded to needs of their own, and the sand crabs came and went despite my imprecations. At times I’d look upon what was the perfect castle with a branch atop it where I could hang a flag, only to see its main gate collapse as one of these swirling sea insects rose up between its crevices, bringing hours of work down, leaving all I’d built, insult to injury, to the ocean, that soon after, would make what was once the beginning of a city into wet flatland again. “And the sun also rises,” said my father, trying to get to the nature of the cycle of life in which nothing was or could be permanent, but I’d sulk away — to the wreck.

The wreck was my greatest solace and may have laid the groundwork for my later fascination with the Titanic disaster. In the later 1930s some great storm from the north, one of the Nor’easters I struggled to comprehend, swept meanly down across the eastern Atlantic coast. The lighthouse we walked to was ruined and rebuilt, as was much of the boardwalk. I worked to imagine the huff of this storm and the great curved waves it made. One such wave struck a small freighter, and it was struck again, tossed and battered, eventually lodged literally into the sand of this now tourist beach. You could see skeletal metal rise from the sand and the outline of the wreck was cordoned off by red tape. Lifeguards whistled furiously if swimmers got anywhere near that area.

I’d walk to the ocean’s edge to stare at these jagged pieces of wreckage, and feel that it was true: some things were beyond repair.

But I was not a swimmer, and perhaps too tiny to matter to the college lifeguards. I’d walk under the tape to the ocean’s edge to stare at these jagged pieces of wreckage and breakage, to remind myself perhaps that it was true: something could break and not be put together again, like Humpty-Dumpty. Seeing these rusty ribs of metal at least took my mind away from the most recent lost castle and the crabs and waters that had conspired to take away the marvels I’d made.

“Be a cheerful boy,” my mother would say to me on the worst of these days, but I’d memorized a scowl, or what I thought was a scowl, and sent it her way. She insisted on smiling as if even my scowling was ineffective.

When I went with my father to get taffy and new flip-flops, the cashier called me “dearie,” and I said, “The ocean ruined my castle,” perhaps my first and most coherent English sentence to a stranger, to which she replied, “Get used to it, dearie. Lots of things don’t go your way,” and having said this, handed me a free candy bar. I was so grateful I burst into tears.

“Don’t worry about him,” my father told dismayed dearie, “he’s an emotional child.” They chatted briefly about difficult children.

And listening to them I was amazed at their failure to understand. For at that moment, with the candy bar and some sympathy, I was the happiest ruined castle builder ever hatched and allowed to walk on the wreck-spiked earth.

— This is one in a loosely linked series of autobiographical essays in which the author recollects his childhood years, spent largely in Washington, D.C., and Madrid, Spain. Some names and details have been altered for reasons of privacy.