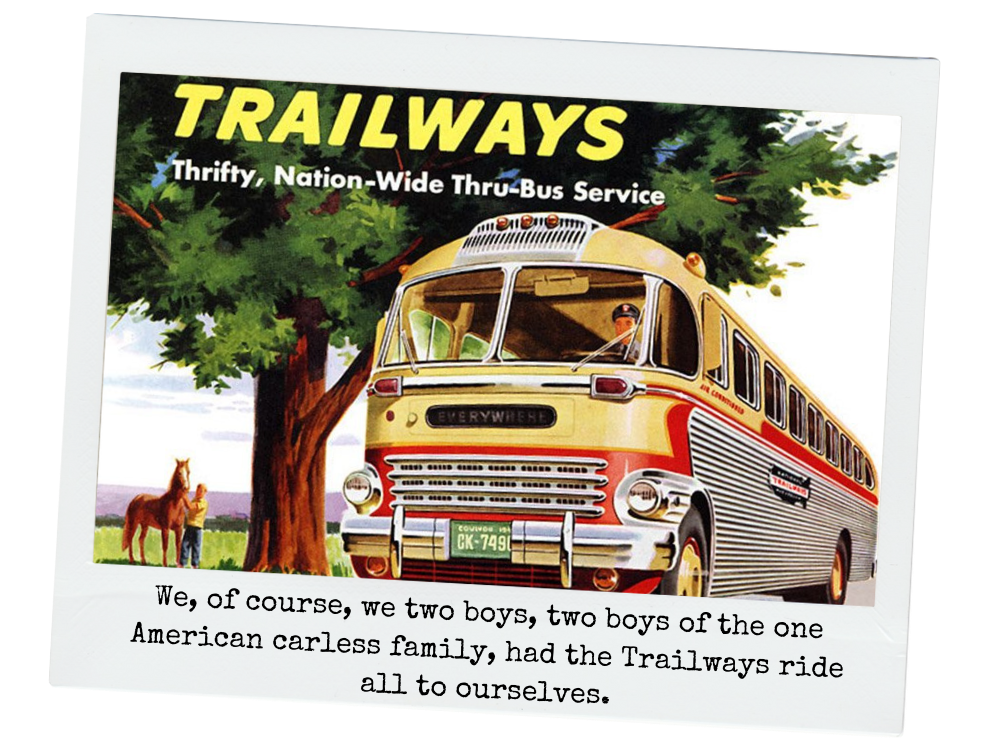

To get to the little yellow cottage by the big Atlantic sea required a bus that made many stops and was operated by a company called Trailways. The bus terminal was in a squalid nook at the center of the city, mostly occupied by people who, in 1959, were known as Negroes. These were my favorite kinds of people because they paused to talk to me, men and women alike, apparently because they found my little white culottes amusing and made no end of joyous fun of my still-ill-formed English, one driver calling me Frenchie, and asking my father to find out how little Frenchie was doing. My father let all this unroll because he wanted me to meet humans as he knew them and as they were: various, of all colors and humors and vapors and faiths and calibrations. The more I came in contact with the world around me, the better, since this also gave his eclectic stories of his own madcap past more credibility.

My mother, the self-styled princess, would not travel on these buses, let alone take a taxi to that part of town, which was not for her. She would join us later, when some friend drove in the direction of the coast or she found a neighbor willing to make the five-hour trip there and back in exchange for conversation with a stylish European lady.

My father wanted me to meet humans as they were: various, of all colors and humors and vapors and faiths and calibrations.

We, of course, we two boys, two boys of the one American carless family, had the Trailways ride all to ourselves. All the drivers were white, and I pondered this casually, wondering at first if all my Frenchie friends drove other routes or if perhaps something else might be afoot. In 1959, I had not a clue about racism and when I heard one man use the word “nigger,” I wondered if that might be the name of an avenue, or a building, or an expression Americans uttered aloud when they were late or disconcerted. My father said nothing.

The bus took just over two hours and sent us along a route with a number, 50, past big green signs indicating where to turn for towns like “Nectar.” We passed through Maryland and across the majestic Bay Bridge, a vast criss-cross of connected architecture that was bigger than the biggest of dinosaurs and allowed us to cross the Chesapeake Bay, which in my little “carnet” of notes I wrote as CHESNEEK BAI, with a less than elegant sketch of the bridge’s connecting segments. After the bridge we paused at a rest stop, which I understood as a “rest pot” and wondered about the why of the pause. When sandwiches and burgers were served I came to my senses, all the more so because all the people serving us were Negroes, and this again made me smile. Over the years I befriended Natalie, a tall Black woman who with my sandwich brought me a stale pancake from the morning, a gesture I adored because I’d eat anything sweet, stale, fresh, black, or white. My father nodded and made conversation with Natalie, asking where she was from, and she said ’Bama, a place I immediately inserted into my fantasy realm as an independent nation that served only pancakes, fresh and stale, and was populated only by tall Black women who had come to know the importance of a smile.

Back on the bus, I played word games with my father. He would say a word and I would have to define it.“Bloon,” he said, and I said a monkey that lived only in the desert. “Misercat,” I said, combining a French word with an English one, and he replied a man who wears pantaloons at night. This we did to pass the time, through towns named Wayville and Denton, towns that to me seemed like nothing more than a few houses, a store, and maybe a railway crossing. These I loved because the bus had to stop when a passenger clanged and, for some reason, all would begin speaking to others, whole rows of gab, Black and white, no distinctions, laughter instead. All of which stopped when the clanging did, and then the bus continued, as if we’d hit some sort of universal peace moment on our way to the waves.

We’d talk about the waves, or my father would, of their metallic color and tolling on stormy days, looking to him along the length of the beach like humpbacks landing by the millions, occupying America in some secret watery form. He said he had once seen a wave that looked like a giant boxer with curvature of the spine. I did not fully understand either word, let alone the anatomical concept, but I knew this was but a preamble to a story, and it was.

Natalie was from ’Bama, an independent nation that served only pancakes, and was populated only by tall Black women who smiled.

During the war, said, he had crossed the North Atlantic on a convoy freighter. Bored and sick below as the vessel belched through storms, he broke all rules and managed to pry open a door to get out on deck. This was strictly forbidden, above all because some men might be tempted to light a cigarette, which a U-Boat periscope operator would see, and that would make the beginning of the end — ships not sunk by loose lips but the burst of match in the pitch black of a stormy ocean night.

In any event, my father continued, he did make it to the deck, but the seas were immense and he was almost immediately knocked down by a wave. He felt at that moment that all was lost and he would be washed overboard, along with whatever else that gulp of wave had taken from the pitching vessel. He was rehearsing the act of drowning — this is how he put it — when suddenly some vast clutches of flesh surrounded his lower abdomen and he was pulled back. It was a sailor, on watch. “Are you mad,” said the sailor, screaming for him to get down below. He was all but tossed back into the innards of the ship, where he was confined for the rest of the convoy.

Later, he met the huge man who had saved his life, by the name of Hayden — Sterling Hayden, a name that would mean not a thing to me until I later came to love films, thanks to my father, and watched Hayden’s second life blossom on screen as a Hollywood actor. See “The Killers,” see “The Godfather” (he plays a corrupt Irish police captain) and you will see the older version of that young man on the deck of that freighter that somehow made it to England when very, very many did not.

This was our time on Trailways, until the driver pulled into the depot, a block from the yellow cottage, and my father would stare out at the Atlantic, as if to salute it, while I coveted taffy. And together father and son walked the short block to open the cottage for the beginning of our June season.

— This is one in a loosely linked series of autobiographical essays in which the author recollects his childhood years, spent largely in Washington, D.C., and Madrid, Spain. Some names and details have been altered for reasons of privacy.