There is no knowing why they picked that house, little more than a shy yellow cottage recessed from Wilmington Avenue — not an avenue but a narrow street, just three blocks from the endless magic of the Atlantic Ocean — a restless ocean that from time to time had flooded the avenue, when storms came from the north in winter. Nor’easters, they were called, but I couldn’t fathom such dialect, barely liberated from the French I’d learned before coming to the United States in 1957.

This little yellow cottage would be our beach home in June for three years beginning in 1958. Apparently my parents had scouted the Delaware seaside town and come away at peace with its tone. My mother liked Mrs. Simpler’s restaurant, which is where we dined every night. She thought Mrs. Simpler’s folksy charm was peasant-like, open-hearted and French. Since my mother, busy becoming an American citizen, was also tentative with the language, anything that reminded her of Europe made her feel more at home.

My father liked that the kiosk near the bus depot just a few feet from Mrs. Simpler’s got the New York Times and Washington Post each morning, which meant he could rise, as was his custom, when the dawn levered the first trinkets of sun, take a walk, and wait for the papers to arrive. He also liked Sal, who had a pizza place, because Sal was the son of a Calabrian woodsman who emigrated in 1907. Sal Salvatore was born in New Jersey in something like a semi-slum outside of Hoboken. But the pizza was good and ample. This I can vouchsafe.

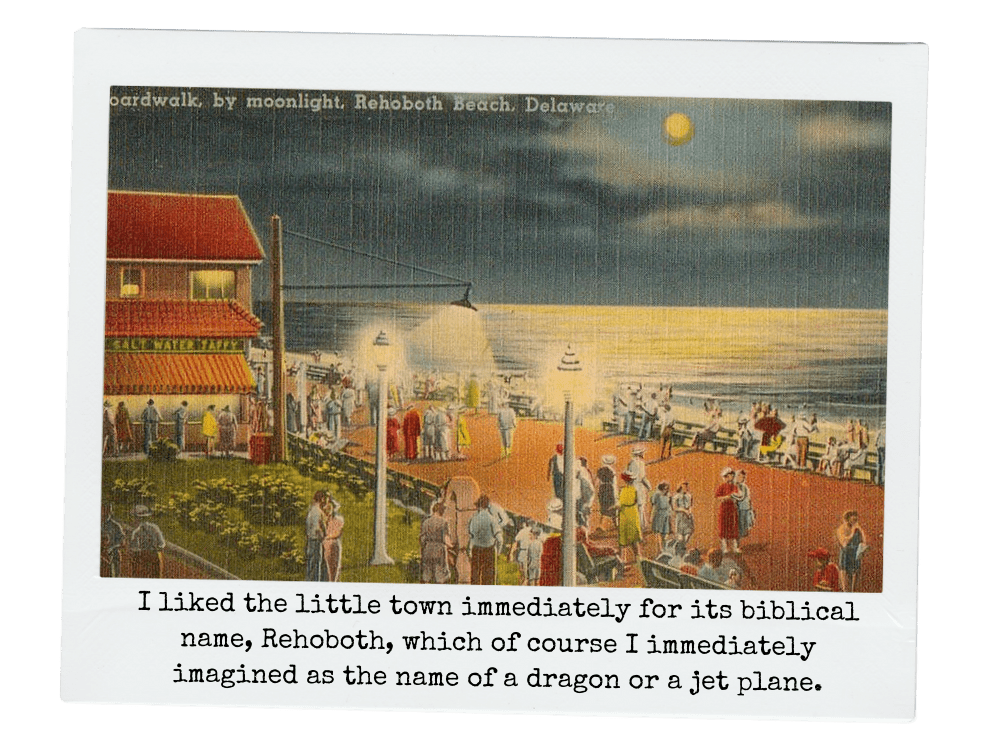

The seaside town was a staple for Washingtonians who wanted out of the political jungle for a weekend or a month. They came, and behaved very well, men in ties on the boardwalk, something my father appreciated, since he never left home without a suit and tie unless he was headed for the beach. But in the evening, when strollers took their promenade, that was the cotton candy boardwalk; many were formal, and the women were in pretty flowered dresses.

The boardwalk was a special place because it was wooden and not concrete, and you could see between many planks.

This is the 1959 I remember, my first vision of America on vacation.

I liked the little town immediately for its biblical name, Rehoboth, which of course I immediately imagined as the name of a dragon or a jet plane. I had never read the Bible and knew nothing of what it contained, aside from a bearded man who gave orders likes the ones I was, in turn, also given from time to time, but in language less arcane.

The boardwalk was a thrill, in particular because it contained Funland and its pinball machines and rides and cotton candy and a taffy vendor, and its “quarter and dime men” with their pouches full of coins, so that fathers would change their paper dollars or half-dollars to smaller coins and let their children run amok among the machines.

The boardwalk was also a special place because it was wooden and not concrete, and you could see between many planks and sense the noise below. Within a few days of my first day there, I jumped down to investigate and found a card game in progress in one place, and in another, a boy with his mouth planted on a girl’s lip. I understood neither the card game nor the lip-planting. Still, these under-boardwalk Americans had a deeply sandy flair and I liked rummaging among them.

At Mrs. Simpler’s — dinner at 6:30 — the meals were ample, with fresh mashed potatoes and greens I hated and nibbled at. One young waitress, a college student (as they all were) took pity on me and passed the word to the other girls: that little boy hates greens. So we reached a silent pact. I would nibble, wink, and one of them would come by and say, “Finished,” and remove those atrocious green “things,” all this to the chagrin of my mother and the delight of my father, who liked my secret pact, and may have liked the presence of the young waitresses as well.

The days were carbon copies of each other (a phrase now outdated, from the typewriter era): we’d rise, father and son, and walk to the beach, where we’d spend most of the day. My mother would follow later, applying her fashionably late rules also to her beach presence. She looked so magnificently glamorous with her blonde hair and trim figure that other women looked at her in envy, one once coming by and asking, “Excuse me, but are you European? You are so stylish.” My mother nodded graciously, absorbing the sing-song of praise, and it came often. She was the princess of our beach quadrant, and though she never did any more than tap-dance in the tide, never swimming as my father did, she was the favorite of the lifeguard, yet another student from the nearby university, pride of the state of Delaware, which to my mother, despite her American aspirations, fell short of the Sorbonne.

After the last plank there were only sand dunes and all manner of assertive reeds that grew to the height of a man.

On the beach my father read what he had yet to read in the newspapers, also showing me with great precision how to turn a newspaper page in the wind, which involved folding the pages in half first, and seemed to me something like a craft. The newspaper itself flapped in the breeze as if unsure whether to leave its owner and head to sea with the news or sit still while its pages were fondled and turned.

After dinner we’d walk the length of the boardwalk, my mother only halfway, with the lighthouse to the north and the last plank in the other direction, after which there were only sand dunes and all manner of assertive reeds that grew to the height of a man. My bedtime was before nine, and what my parents did after I did not know, since at the beach (perhaps for the first and last time in my life), I slept well.

There may have been a reason for this sleepiness, in that a month was a long time and demanded adventures and schemes and secret jaunts, some of them plotted at night. There was no television in the cottage and my father’s craving for news was satisfied only by the papers.

To say it was another world seems an understatement. From my vantage point sixty years later, it was another planet, perhaps another galaxy.

And part of the fun was getting there. But it’s nearly nine and I need to turn off my lamp, so my travel odysseys will have to wait until tomorrow, when the waves of my memory wake from their salty slumber.

— This is one in a loosely linked series of autobiographical essays in which the author recollects his childhood years, spent largely in Washington, D.C., and Madrid, Spain. Some names and details have been altered for reasons of privacy.