If books end, so do phases of life, though they refuse to stop blending, one with another.

The London excursion to see Mr. Foyle, who ran a rare book shop (long gone) off Charing Cross Road, was a great success. Mr. Foyle was a thin and busy Englishman between thirty and eighty who could not get enough of inquisitive teenagers, and directed me to postcards of liners past, which I spent hours leafing through. I could have made a home in his shop. I used my paper route money and my father’s good graces to pick up loads of cards and snaps of vessels from another time. Foyle could not have been more delighted to find a child who liked maritime history. It was another time of the world.

The best would come later, some six months later, when Morgan Robertson’s novel reached Washington and I attained the nirvana of having it. I remember its color, red-orange, and that his narrator survived the sinking of his fictional Titan only to end up on an iceberg, where he did battle with a giant bear. Nice touch, if silly.

But by the occasional light of London’s restless days I could see the sickness creeping over my father’s face, and noticed his slouch when walking. Perhaps it was the time spent with Mrs. Margaret and so much time with the dark yin and darker yang of cancer, which gradually steals items from a being’s inner mantlepiece.

My father did not say a word but I could now tell I was fourteen and he sixty-eight, just as I now know for myself that it is time to compress and accelerate. An Eliot line comes to mind, “Hurry up please, it’s time,” though I knew nothing of Eliot at the time.

We went to Greenwich and saw the models of old ships and walked small streets on rare sunny days. I still sought out my baseball box scores from the tabloids, though they were full of England’s World Cup successes.

Mr. Foyle was a thin and busy Englishman between thirty and eighty who could not get enough of inquisitive teenagers.

London seemed more in motion, more vibrant than four years before, as if someone had taken a blind man’s fingers and collectively plugged into wall outlets, lighting up the culture of the so-called “happening,” the jolt moving culture’s tectonic plates in a way that music and art and theater all brought to the fore. Bob Dylan played on the BBC and attained a demi-god status he seemed bored with. The Rolling Stones continued their cynical march, waiting to paint things black. Under it all, money-making boomed, and this was the most important thing of all, at least as a lesson to those on the other side of the much talked about Iron Curtain.

So it was that I went behind the curtain, flying from London to West Berlin for a two-day stay that included a tour of East Berlin, that Darth Vader territory indirectly ruled by Moscow, that wished to truncate the joys of cash and was laughed at when it said money wasn’t everything. Easy to say when whole populations are in jail, or so went that lyric. I tried to take this all in, the ideological quarrel, but failed. Instead I played onlooker.

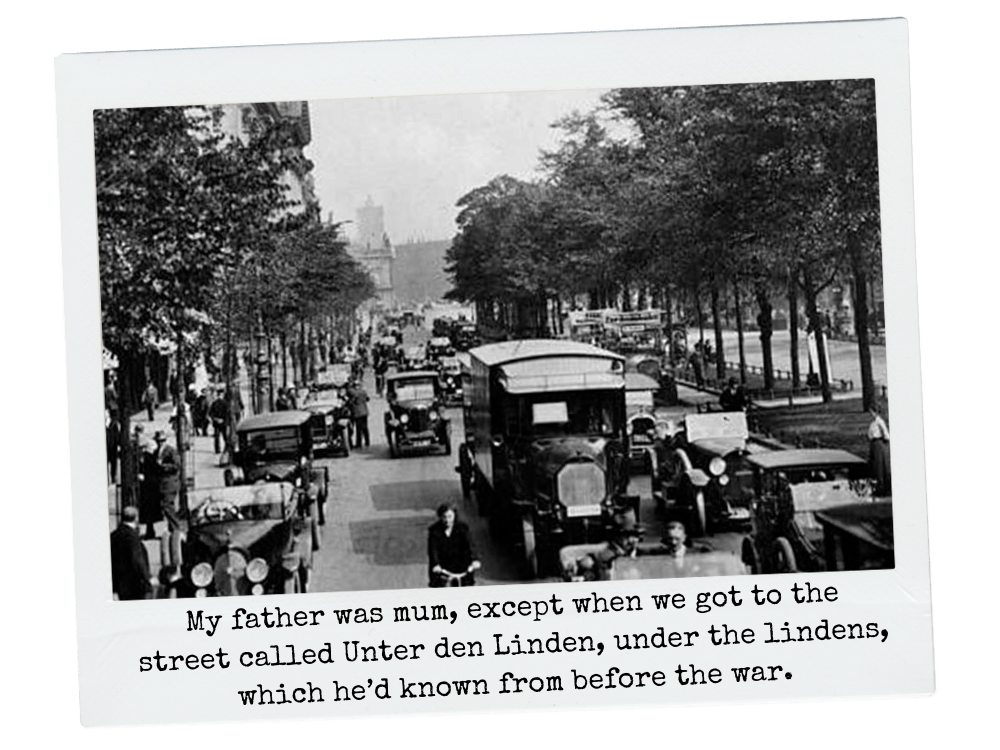

What I saw when our bus crossed the checkpoint into East Berlin, and therefore East Germany, was a still half-bombed-out city with a heavy patina of grime not even the pretty East Berlin guide could talk away. “And this,” she said, pointing to a dilapidated hospital, “is a model of medical care, since all citizens are taken care of here.” It was difficult, looking at the thick slabs of concrete, to know for sure if she was speaking sincerely, from a script, or inserting sharp irony of her own making. My father was mum, except when we got to the street called Unter den Linden, under the lindens, which he’d known from before the war. He’d had cocktails with Göring in these parts. Very charming man, Göring, until you grasped the fullness of the landscape, which Hitler framed in one-way-only terms, his way. Still, Göring had good table manners. Perhaps Pol Pot did as well. Yet once again, I was not yet aware enough of the world’s pendulum to understand just what I was being told. Instead I gazed at the trees and wished for squirrels. None came.

At the end, the sunny guide said she hoped we’d had a nice time in her beautiful city and hoped we would tell others about socialism’s wonders. We should be mindful that propaganda was just that, and we had just seen the real thing with our own eyes. If only what we’d seen, or been permitted to see, didn’t appear so entirely sad, a sadness broken only by the occasional pedestrian who smiled at our group and waved. Given my father’s sullen looks I preferred to dwell on that smile and recollect the days of Spain, when all seemed so alive. Those days were only some four years old but they seemed to come from another century, as if the batido had gone out of style decades ago. But these may be the wages of fatalism, the cost of cheer when it begins to run out and the bill comes due.

The secret mission portion of our journey, to Rome, came next, but it soon turned anti-climactic. I saw my mother alone and we chatted in a stiff way, with the stiffness mine and mine alone, as always taking my father’s side and showing no signs of capitulation. She invited me to come and live in Rome and attend school there. I scoffed at the idea and sought to leave as soon as I could, to be among the lizards in Villa Borghese, not far from my mother’s flat.

My father’s meeting was successful in a manner of speaking in that he persuaded her to return in the fall, a one-more-try effort so I wouldn’t be alone. If only either of them knew I really wasn’t alone because I did not dwell in their world but in one of my own elaborate making, and still do.

My mother’s return lasted only a few months, until spring, and off she went again, this time for good.

My father seemed pained after his marital negotiation, and so I played the role of cheerleader. I asked him if he would help me find a nice sweater for the winter since he had such fine taste, and off we went into summer sweater-hunting, quite a trick in Rome. It proved distraction enough to get us through a day, then another, before the flight from Rome to New York on TWA, whose captain (in the days when captains still had a voice) spoke of the different kinds of clouds we were seeing and foresaw a time when travel would be supersonic. He was right, of course: Concorde came. Amazingly though, it didn’t last. People lost interest in such marvels as rocket planes, too busy tapping away for information, sending dispatches about their moods, making public thousands of images of their dogs. With communism gone, boredom set in, filled by a newer and bigger lust for money, and, biggest of all, a desire to be made afraid again, to then be made to feel secure, whether against terrorists or viruses. With communists gone, a hole opened up, and I watched as strange things filled it, many marvelous and intense, others seeming like little surrogates. But a big war was no longer possible, so we moaned instead about the planet falling apart, as if it might assuage the guilt that comes naturally with affluence. Guilt and sadness, so that decades after my thirteenth year, many people seemed as sad as East Berlin once looked, able to make ends meet thanks only to special new mood drugs. Again, the batido was lost in the mix.

My mother did come back that fall, true to her word, but nothing at all worked and Christmas was a pageant of silence or quarrels, at times a hash of both. I rode my bike and joined the Boy Scouts, a troop that met every Friday. I learned a true Scout should be trustworthy, loyal, helpful, friendly, courteous, kind, obedient, cheerful, thrifty, brave, clean, and reverent. No mention was made of throwing salt over your left shoulder if you spilled it at a Spanish villa, and this dismayed me. Where was the folklore, and where was Telefonica, which had gone missing from my dreams.

Perhaps the parental squabbles squeezed out the port and the cables. In any event, my mother’s return lasted only a few months, until spring, and off she went again, this time for good. I would not see her again for four years.

I sometimes thought of Sam, because I’d reached the point, if only barely, that her body and its parts, and above all her voice, meant something to me. I thought also of Marcia and wondered who she’d married, because that was what you thought about women. I tried that once and it lasted nine weeks.

As my father worsened, his resolve to work on thickened, making things worse when he was rebuffed time and again. He deserved better, but soon the Stones would rightly be singing, “you can’t always get what you want….” In fairness, the lyric also suggested trying might get you what you needed, but I saw no evidence of this with my father.

I was midway to fourteen and old enough that my father’s doctor, a wonderful man, would take me aside and say, “It kills me inside. This disease is a bitch,” and he’d cry. But the tears weren’t simply about my father. His beloved wife had a kidney ailment that was killing her, and did kill her, leaving him to stare at me and say, “Here I am, a doctor, what I always wanted to be. And I couldn’t do a thing for Rita, not a thing. And your father. ’Tis what we’re supposed to accept on this planet but it’s shitty.” This from a man who’d been a medic on the flight deck of carriers in the Pacific when waves of kamikaze planes slammed into decks, leaving dozens of sailors running around madly ablaze, some of them simply leaping once and for all into the sea. “Better choice than what I could do for them.” Many in flames skull-deep.

Trustworthy, loyal, courteous, kind.

I tried. I still do.

I do, some days, want back the pre-DiDi days when I was alone with Entonces by the pylon, playing our little games of chess. I want back the wood paneling of the DC-7 and boarding a flight from tarmac to plane, no questions asked. I want to kiss in a garage when no one’s looking except a snooping nine-year-old, who if I saw him I’d smile at. I want in times of stress and distress to climb the telephone pole to the top or find my way to the summit of the roof, this time wishing and hoping no fire department ever gets wind of me, and there I’ll be, starting out and up and all over, until I can see no more and the whole of the magic world turns to the kind of black you can not only live with but might actually wish to.

— This is one in a loosely linked series of autobiographical essays in which the author recollects his childhood years, spent largely in Washington, D.C., and Madrid, Spain. Some names and details have been altered for reasons of privacy.