My much-anticipated VC-10 adventure did not go quite as planned, and yet again, it was my father’s uncanny sense of my mood that had much to do with it. When we returned to the hotel from strolling by the liners I buried myself in baseball box scores, trying to catch up on what I’d missed during my Walter Lord Titanic reverie. I paid little attention to my father, who was speaking about flights on the hotel phone. I assumed he was checking last minute details.

Not so.

The next morning when I rose, bag packed, he said, “We now have one more day in New York and it belongs to you.”

I was mystified, even miffed. I wanted my plane.

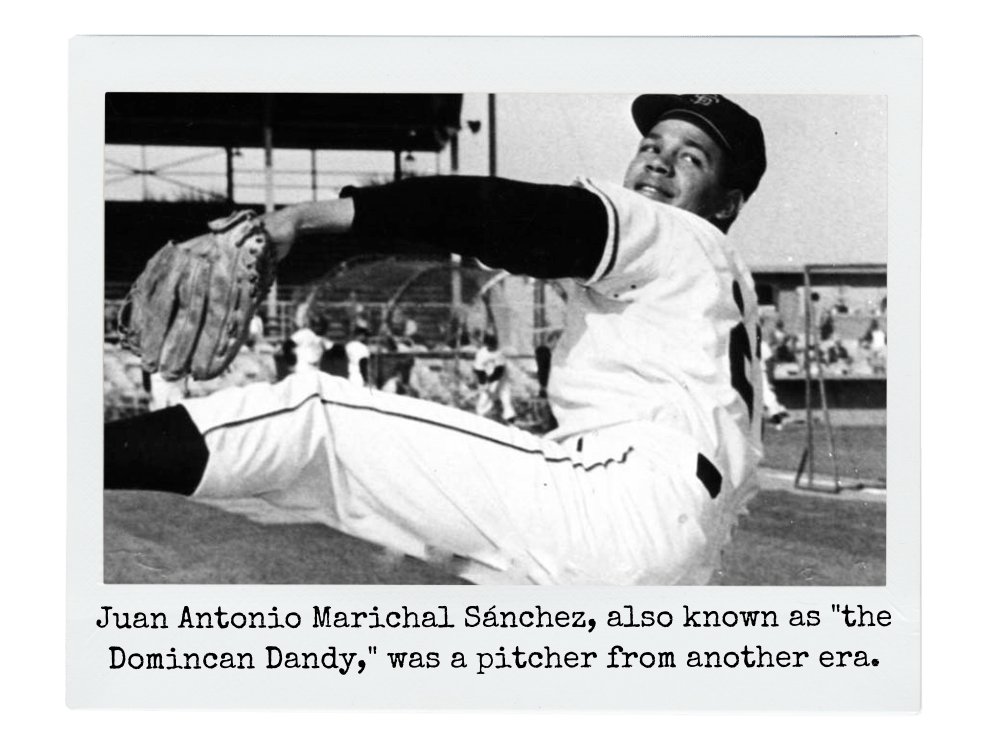

What I received instead was a ticket to a baseball game that afternoon at Shea Stadium between the New York Mets and the San Francisco Giants. Somehow my father had overheard my admiration for Giants pitcher Juan Marichal, who seemed to pledge his arms and torso to the sky before throwing a pitch.

That morning my father had found a ticket outlet. The night before, he’d checked on availability and changed the flight by a day. We were in no hurry.

I was thrilled. But how would he, this intellectual dynamo, manage in a stadium? He wouldn’t.

“You are thirteen, I won’t be here much longer, to get to the stadium….” And from there he listed subway trains, the D train foremost among them.

I knew better than to question his comment about his mortality. We had a pact in that regard. Sentimentality was to be kept at arm’s length. He was sixty-eight (my age now) and ailing. I was wholly thirteen, skinny and wildly freckled. To insist, in Hallmark greeting card terms, that he still had a long and prosperous life ahead of him would have been to insult his vision of life as a time-constrained excursion, a vision our thousands of conversations had led us to share.

I took the ticket from him and recognized it for what it was, a rite of passage, and I followed all the directions to the game, sat among Marichal’s partisan Dominican fans who saw him as their Generalissimo, their Mostest, and with no end in sight chanted Mar-i-chal, Mar-i-chal, beating many small drums. But it was the Mets that beat up on him, his Most-ness set aside. On this day the sky and his limbs were not in sync and the Mets got him out of the game early, eventually winning 9-5 – and the Mets did not win often in those days.

On this day the sky and Marichal’s limbs were not in sync and the Mets got him out of the game early.

I left in the eighth inning to get a jump on subway traffic, but also so I could dine with my father and we could share the pleasure of this day he’d given me as my birthday surprise. My father had paid scant attention to his first son from a second marriage, a son from whom he was now all but estranged, and this love affair with little me seemed openly compensatory, an atonement of sorts. But these are thoughts I came to later, when I began probing the impossibly complex circuitry of families small and large.

The VC-10 tried hard to look the part of a beautiful jet and it succeeded in all respects. Its double-engines on each side of the fuselage just beneath the tail were elegant, unobtrusive. The forward thrust of the plane came from behind, and not from the wings, giving take-off a more forceful music. This was one jet that seemed eager to fly.

But no sooner had we taken off than a stewardess approached us and asked if my father would be willing to give up his aisle seat in the forward section of the plane to a sick woman who, for whatever reason, did not want to sit in the back, so close to the engines and their loud thrust. My father signaled for me to sit still, and I suddenly found beside me an aging lady who seemed both weak and withered. “Thank you both,” she said.

She then said, “What a handsome boy and fine grandfather,” all but forcing my hand: “He’s my father.”

“All the better, you’re lucky to have each other.”

But what I sensed coming, questions about my mother, our destination, who we were, never came to pass. Instead, she said:

“I’m sorry I broke you and your father up that way. I would never do such a thing. But, you see, I’m dying of cancer and this is my final trip to see my grandchildren. I know I won’t be going back because it’s in its final stages, and I have stopped fussing about it. I just want this final trip.”

Her confession began a many-hours long chat about disease and mortality and the pleasures of life and how youth should be lived at full throttle. She had once been an advisor to a California senator so we spoke of politics and communism and how obsessions about evil adversaries could turn into a disease of their own. She spoke of the Joe McCarthy “better-dead-than-red” era with a sigh; friends of hers had been blacklisted. I told her how my father had been the only man investigated by McCarthy as a Fascist because he’d been the first American to interview Mussolini and at first written flattering pieces, before picking up on the slow-rising stench.

She called herself Mrs. Margaret and she never did give me her surname. “The thing about this disease,” she told me, “is that it nags; it eats little bits of you at a time before spitting the whole of you out.” I didn’t dare mention my father’s cancer, since our father-son watchword was discretion, born of his “loose lips sink ships” wartime attitude toward distributing intimate information casually.

But as the hours passed, Mrs. Margaret grew on me, less like a mother than a trusted aunt. When I mentioned my life and times in Washington, my bike and paper route, she said one of her sons had actually bought his bike with paper route money. This cheered me, since I’d done the same, also buying a transistor radio. Though my father gave me a weekly allowance, he’d always emphasized the need to understand what it meant to work, because without such an understanding money would always seem abstract or in short supply, and griping about money would take its place at the head of the table.

“A smart man, your grand…”

And we laughed, before she began coughing, and the cough brought out blood that I dabbed off her skirt and the facing seat.

Nothing good lay in store for her, I knew, or for my father, and eventually I’d receive some sort of knock on the door I couldn’t not answer. And notwithstanding the blood, or maybe because of it, she laughed again.

“Cancer! Whoever invented this was very much an advocate of population control…”

She said: “There are all these wonderful drugs now, and they’ve transplanted a heart, and soon they’ll get some men on the moon, but we little humans will keep on suffering in the same old ways. Maybe in the future we’ll live a little longer, but after a certain, really, who cares? You just promise me you’ll have a good time being thirteen!”

She began coughing, and the cough brought out blood that I dabbed off her skirt and the facing seat.

I promised, though the fact that my mission in London was to find a rare book didn’t sit entirely well with her. Go see theater. Go see a movie. Walk around the park. Just be careful crossing the street.

It was my second trip, I told her. I was a veteran. She then astounded me by turning to sports, not baseball, but sports nonetheless. “You know, you’ll be there for the World Cup and this year it’s actually in England. Can you imagine if they win!”

They never win, I told her, but three weeks later that is precisely what they did, lifting a monarchic nation ruled by rock’n’roll, Twiggy and Beatles delirium into an improbably wild state of collective joy.

By the time I stopped talking to Mrs. Margaret the plane was into its London descent. When we landed my father came forward to fetch me and leave, but I couldn’t.

A wheelchair was coming for Mrs. Margaret and I wanted to wait for it. She’d given me too much not to repay her with any affection I could muster.

As the jet emptied, she turned to my father and said, “This is one remarkable boy you have here. He just saved my life on a flight I’d been dreading for months. This boy’s a keeper.”

To which my slightly embarrassed father knew only to say, with typical dry wit, that he fully intended to keep me, at least for a while.

Then they came and wheeled Mrs. Margaret off. I never saw her again.

Six months later, just before Christmas, I received a note from an unknown address in California. It read, “The lady of the house passed in October, and I only now found this little note of hers telling me to write to you when it happened, just to wish you well. I know she liked you a lot and never forgot that plane ride.”

Out of sight of father, sofa, kitchen, cat, squirrel, and all other things of substance, I wept.

— This is one in a loosely linked series of autobiographical essays in which the author recollects his childhood years, spent largely in Washington, D.C., and Madrid, Spain. Some names and details have been altered for reasons of privacy.